In August 2009, Los Angeles Times reporter Jason Song had just finished the investigative series “Failure Gets a Pass,” about how difficult it was to fire some teachers in the Los Angeles Unified School District.

He had his first byline at the newspaper as the school district reporter in November 2008. The series garnered a lot of attention, and Song’s editors asked him to keep the ball rolling, to find something else to investigate. They paired him up with experienced education reporter Jason Felch, and together the two decided to examine elementary school standardized test scores using a value-added method of evaluation, which evaluates teachers by comparing the improvement in individual students’ standardized test scores.

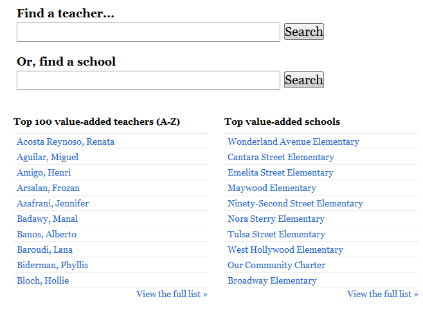

In the next year and a half of reporting, Song and Felch interviewed more than 100 teachers and principles, produced a database of more than 6,000 teachers with their effectiveness ratings and reported a currently on-going series called “Grading the Teachers,” about the value-added approach, which is not a large factor in LAUSD teacher evaluations. Song and his team obtained millions of test scores, which they hired a consultant to analyze and worked with an in-house database team to organize and explore.

The series, which began in August 2010, has received a huge response, both positive and negative. United Teachers Los Angeles President called for a boycott of the Times. U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan lauded the series and the release of such information. In recent months, universities have questioned the method of evaluation the Times used. The Times received thousands of responses from teachers and parents, some supporting the information and many others criticizing the newspaper for the release of sensitive information.

Twelve years ago, though, Song was an English student at Occidental College with no intention of becoming a journalist. His most extensive print experience was for his high school newspaper, and he applied for Los Angeles Times’ Metpro program, designed to help beginning journalists launch their careers in Tribune newsrooms .

Song’s longest engagement away from the Times after joining Metpro in 2000 was his four-year stint at the Baltimore Sun, where he worked in bureaus and covered higher education before returning to Los Angeles in 2005 and to the Times newsroom in November 2008.

AAJA reporter Sonali Kohli sat down with Song to talk about his reporting experience and the aftermath of the series.

LOS ANGELES TEACHER RATING DATABASE

NO GOLD STAR FOR EXCELLENT LA TEACHING

SK: How did you and Jason Felch come up with the idea for the “Grading the Teachers” series?

JS: Neither of us can really remember who came up with the idea first, but at some point we were like, “Hey, they have these test scores, they exist, and we know they’re usable. Not every school district keeps clean data, and we believe that we can get it, so let’s see what happens there.” And that’s how it started.

SK: How does the process of collaboration work between the database team and the writers who are reporting on the story?

JS: There are just a ton of questions that Felch and I are not really equipped to answer on our own, we need some kind of expertise. I think that holds true for any kind of really big data-driven project-you need to have support and you need reporters who have a different skill set than you might have to look at the data and figure out where the soft spots are, and to test the data to make sure that our conclusions are right.

SK: The stories are very narrative, with you in the classroom observing the teachers. Why was it important to visit so many teachers, even though you ended up using only 15-20.

JS: We’re interested in teacher effectiveness-we want to see what good teaching looks like and we want to see the whole spectrum of teaching … Part of that was us testing the data as well – talking with principals about who their best teachers are, because we wanted to make sure this actually has some basis in reality … We wanted to make sure we were putting the information in the right context. There’s a limit on what you can see-what does good teaching look like?

SK: How did you go about observing individual teachers?

JS: We did it several ways-sometimes we’d observe first then compare to our own information, but knowing that there’s a limit to what we can actually report. Causality is not necessarily going to be totally apparent to us, which is why it’s important to talk to the principles and parents if we could. Since the kids were in elementary school, it’s kind of hard to interview them about how good their teacher is.

SK: How much did you know going into this that it would have the impact and the amount of feedback that it has had?

JS: I think we had a pretty good idea it would be controversial. (Once you get the data), there’s the question of, “Wow, so we can actually do this now? We are about to embark on a very controversial path.” I knew people would read the story, I knew people would have really strong opinions. I never even thought to think, “What will Arne Duncan think of this? How many bloggers will look at this?” That never really crossed my mind. I spent most of my time thinking about how I can make sure the story is correct.

SK: A University of Colorado study was released in December that used the same data and found certain percentages of discrepancies between your results and theirs. What was your reaction to that?

JS: That’s a complicated topic. My basic takeaway was this is fine, this is good, this is what people should be doing. Because we wanted to be as transparent as possible. In other words, if you want to check our stuff we are going to give you the white paper that explains how our consultant did it. If you want to ask LAUSD for the same data that’s great. And we knew there’s no such thing as a perfect value-added system, so you’re bound to get different results using different systems … I think the greater takeaway is that there are different systems, and if you’re going to implement this system you as a school district have to kind of figure out what the best system for you is. Our way is not wrong, the other way is not wrong. There’s not some kind of gold standard.

SK: Did you have a specific goal going into this project of what school districts would do with the data?

JS: I can only control what happens between now and when it goes out into the public view … This is not me trying to push some kind of project. If they want to adopt value-added, that’s fine, if not, I don’t really care. Just as long as they’re open in the process and tell me what they’re thinking, that’s what I want to know. How they actually use the data is not something I can control.

SK: I know you got thousands of responses from teachers. What is your response to people either being supportive, or really blasting the entire project?

JS: I can see where they’re coming from. I’m sure they never thought something like this would ever happen, and so I’m certainly sympathetic. … But in the end it is something we struggled with a lot. It’s a newspaper’s job to publish information. If we’ve checked and we believe that it’s right, I am of the view that we should publish it.

SK: With newspapers like the LA Times suffering financially, how do you fund a project like this and have a team of reporters working on this almost full-time where there are so many other things that need to be covered on a daily basis?

JS: I don’t know. That’s above my pay grade. I think a lot of people saw the promise of the stories. A newspaper has to be kind of nimble, and we have less reporters than we had in the past. So if I’m not covering the school district the way I once did, someone’s going to have to cover it for me, and that’s the way it’s going to have to go. No one said, “Hey write more stories while you’re doing this.” They just kind of said, “Go report.” So I guess the people upstairs thought it would be worth the stretch.

SK: Was this your first experience with database journalism to this degree?

JS: I’ve never looked at something like this where there are millions and millions of records. How do you organize it? That was really more (LA Times database editor Doug Smith). He would give us the raw scores, and we would figure out how to organize it. Do we want to organize it best to worst, organize it by school, how much information do we really need to do our reporting? So we had many iterations of the data because we needed something that we could actually use and take into the field.

SK: Do you think database journalism is going to take a greater role in this kind of investigative journalism? How do you think that’s going to happen?

JS: I think so. Since there’s so much information out there, it’s a question of how do you organize it? So in the case of newspapers, databases just make sense. They can tell you things that you could never find out in a million years on your own … As I read other newspaper series’ and there’s just so much out there in terms of how they organize information. It’s kind of inescapable. And I would say that’s a good thing.

SK: There have been questions from a lot of people about what makes you qualified to put this much out there about teachers and qualify them in these ways. What’s your response to that?

JS: We have reporters here that cover the health care industry that aren’t doctors. This is what they pay us to do. And they pay us to ask questions, to educate ourselves as much as possible … I don’t have a teaching credential or anything like that, but I don’t feel that’s necessary to write authoritatively and to understand the subject that we’re working on, especially since we spent 18 months on the project. I think we’re qualified to write the stories.

SK: Do you have any sort of timeline as to how long you’re going to be working with and pulling stories out of this data?

JS: No. It would be nice to know, but no, I have no idea. I assume I’m not going to be an education reporter for the rest of my life, although I wouldn’t mind that. But there are very long story lists, so it would be nice to tackle that if we could.

SK: What is your reaction to all the attention you’ve been getting?

JS: It’s fine. I mean, it’s a little strange to be on television yourself. The public speaking aspect of this job has been strange, and getting used to being on television cameras and whatnot. To a certain degree we have become the story, which I guess was kind of inevitable. I don’t mind doing it, I understand why they’re doing it. It’s just that … I could not be an anchor or a field person for TV. I just like my notebook.

FOR MORE MEMBERSHIP COVERAGE:

A CENTURY ON, RE-ENVISIONING A 21st CENTURY RAFU SHIMPO: Samantha Masunaga (Peter Immamura Memorial Scholarship recipient/ UCLA junior) talks to editors at the largest and oldest Japanese daily newspaper about grappling with a changing newspaper industry.

LIFEYO: Blogging made Simple(r): Steffi Lau (scholarship recipient/ USC senior) interviews Lifeyo CEO Mike Kai, who founded a website hosting platform that aims to simplify the website-building experience with drag-and-drop features, allowing users to customize content and create a site within minutes.

PATCHING UP THE JOURNAISM INDUSTRY: Natasha Zouves (Sam Chu Lin scholarship winner/ USC junior) interviews AAJA-LA members Patrick Lee (regional editor, LA) and Hazel Lodevico To’o (glendora.patch.com) about working for AOL-owned Patch.